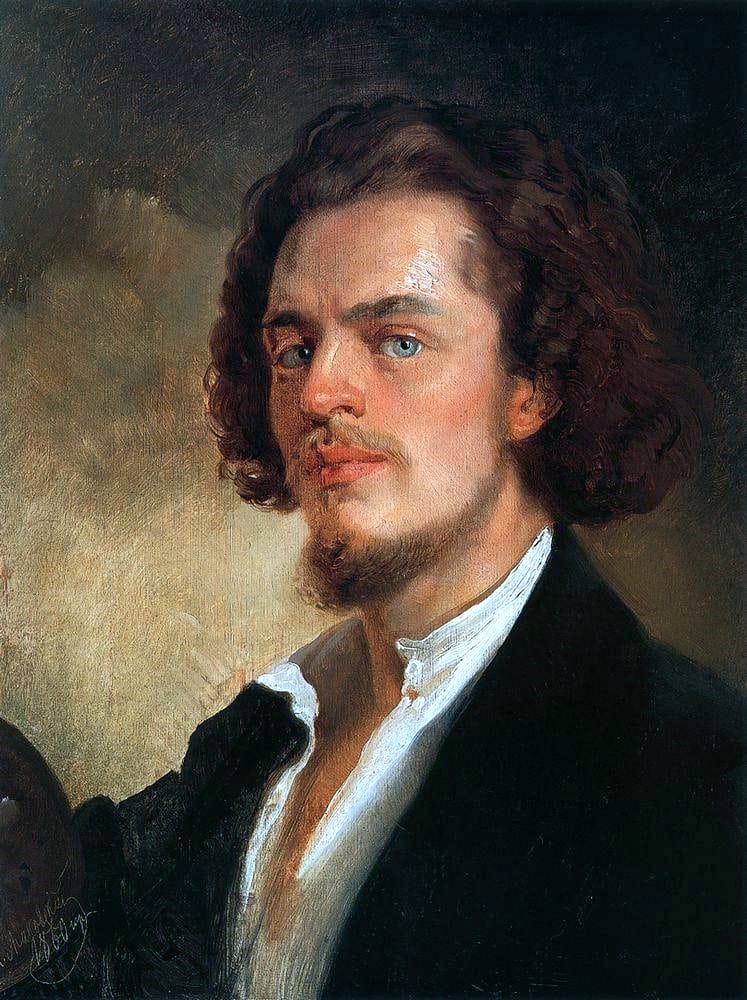

Historic Painting: "A Boyar Wedding Feast" by Konstantin Makovsky, 1883.

This scene depicting 16th or 17th century Russia has more to do with the present than you might think.

It's been more than a month since my last Historic Painting post (which itself had sort of an unexpected reception on social media, see the end of this article for that story). In doing my belated rounds of 19th century art I discovered this gem from Russia, titled "A Boyar Wedding Feast." In this absorbing and vibrant scene, we're in Russia evidently in the 16th or 17th century, and the rather somber-looking bride at the right is being sold in marriage to a member of the nobility while parents, family members and hangers-on toast with various shades of enthusiasm. And evidently they're about to eat an enormous swan served on a platter. A boyar, for the record, was a member of the highest feudal class in imperial Russia, a nobleman or landowner. In this period, the boyars basically controlled Russian society, down to and including the tsar himself--boyars, for instance, put the 16-year-old Mikhail Romanov on the throne in 1613, founding the dynasty of rulers who would continue in power until World War I.

"A Boyar Wedding Feast" was painted in 1883, during the very long period of gestation of the revolution that ultimately took out the Russian tsars. Konstantin Makovsky spent most of his professional life at the apex of the Russian artist class. His father was also a painter, his mother a composer, and the defining decision of his life seems to have been which of these vocations to follow. He chose painting. Educated in Moscow, Makovsky went to France for a while before returning home, where he became a member of the Imperial Academy of the Arts. However, he quit that prestigious institution, together with a group of colleagues, in a famous incident in 1863 called "The Revolt of the Fourteen," which was caused by, as they today say in the music business, artistic differences. Makovsky continued to paint and travel, ultimately winning a prize at the 1889 World's Fair--the exposition that gave us the Eiffel Tower. Many of his subjects, like this one, were scenes from Russian history. Makovsky died two years before the Revolution, in 1915, when a carriage he was riding in was hit by an electric tram on the streets of St. Petersburg. What a way to go.

Though Makovsky's work strove to portray the Russian past as lavishly romantic, modern conditions are not that far removed from it. In a sense, the boyars of old imperial Russia still exist; they're now called oligarchs. Instead of collective farms run by armies of serfs, they own oil companies, and their economic power is still protected by the tsar, who today is called Vladimir Putin. Almost nothing that happens in Russia is new. The past is the country's identity. Accordingly, we can still absorb a lot from old paintings like this one.

So here's the deal with my last Historic Painting post, which featured "The First Thanksgiving" by Jennie Augusta Brownscombe. When it went up on my public Facebook page, it suddenly got a huge amount of engagement and dozens of comments--almost all of them some variation of "Amen!" or "Glory to Jesus!" Most of them seemed to be from people in India, Southeast Asia or countries in Africa. I don't think anyone read the article because no one commented on its contents or even seemed to be aware of its context. Brownscombe's painting, however, includes an image of a man praying with his hands to the sky which seems to have been the trigger. I had no idea it was that easy to hijack Facebook's algorithm with a picture of somebody praying, but evidently that's a thing on Christian social media in the developing world. Not too many history fans in that milieu, though.

The Value Proposition

Why should you be reading this blog, or receiving it as a newsletter? This is why.

☕ If you appreciate what I do, buy me a virtual coffee from time-to-time to support my work. I know it seems small, but it truly helps.

📖 You could also buy my newest book.

🎓 Like learning? Find out what courses I’m currently offering at my website.

📽 More the visual type? Here is my YouTube channel with tons of free history videos.

Comments ()