Deadly poker game: The moral gamble of the Lusitania.

The Lusitania disaster was a terrible collision of chutzpah on one side and naïvete on the other.

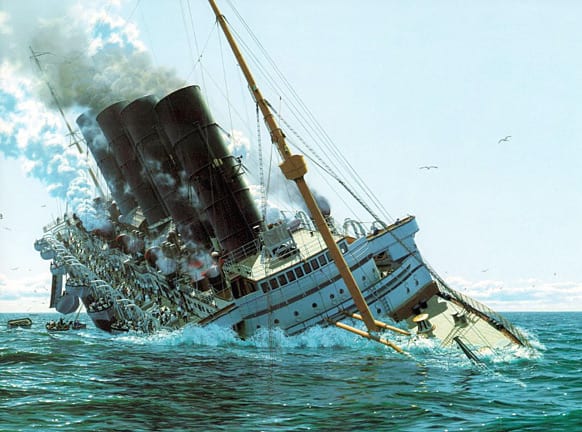

Today, May 7, is the 108th anniversary of the tragic sinking of the luxury liner Lusitania which occurred off the coast of Ireland on May 7, 1915. As is well known, Cunard's Lusitania, then the largest ocean liner still in passenger service, was callously torpedoed by a German submarine and sunk, killing 1,198 innocent civilians in an outrageous act of war. That act began a chain of events which would eventually, a bit less than two years later, bring the United States into World War I on the Allied side. This article is not really about the sinking itself. Instead, it's about the curious psychology surrounding the Lusitania, and why it was really a very tragic case of chutzpah on the part of the Germans colliding with naïvete on the side of the British. That subject may sound arcane, but I think it's an interesting glimpse into why World War I was so traumatic, and why the Lusitania disaster is viewed as such a turning point in history.

First, the facts. At the end of April 1915, Great Britain and Germany were about to enter the tenth month of the destructive First World War, whose major front in France had bogged down in muddy trenches the previous September. The British fleet blockaded the German coast, effectively bottling up Germany's navy, except for one specific kind of ship: submarines. By early 1915 Germany had only just begun to use submarines with any regularity. The submarine--the Germans called them unterseeboots, or U-boats--was such a new weapon and nobody really understood how they might work tactically or strategically. Were subs best used as a defensive weapon? Or could/should they be used to target supplies and food coming into British ports? The Germans seemed to want to at least give that a try, but their efforts toward this end in the early months of the war were, in the scheme of what was later to come, fairly small-scale.

For their part, the British weren't that concerned about German U-boats, and not only because they also didn't really understand how they might be used. The British feared raids on their commercial ships by Germany, but they expected these raids would be done by surface ships. Prior to April 1915, with only a few exceptions German submarines had tried to attack only naval vessels. Cunard, Britain's biggest passenger line, had one of the few big ships still left on the North Atlantic that hadn't been pressed into duty for the Royal Navy. That was Lusitania. America wasn't at war in 1915 and people still needed to get back and forth between England and the U.S. Although bookings were naturally down due to the war situation, Cunard decided to keep Lusitania sailing. After all, even if the Germans had the capability to attack a huge passenger liner, it wasn't very likely they would elect to do so--and even if they did, Lusitania, which had once won a speed record, was far faster than the fastest clunky U-boat, and could easily outrun a pursuer. The risk seemed minimal.

On February 4, 1915, Germany announced that it was declaring the seas around the British Isles to be a war zone, and that its submarines would try to sink any ships belonging to Allied nations (principally British or French). Honestly this was more bluff than anything else. Standard procedure for sinking enemy ships in 1915 was a sort of Benny Hill Show type of procedure where the aggressor would come alongside, declare its intent to sink the ship, allow the target ship time to offload its people into lifeboats and get a safe distance away, and then fire torpedoes. Germany recognized this procedure was pretty unrealistic in the age of modern warfare, but tough talk of ignoring it was one thing, where actually doing it was quite another. If you were a German U-boat captain, would you give the order to torpedo a defenseless passenger ship filled with women and children? The British simply didn't think the Germans would do it.

Herein lies the deadly game of poker that both nations were playing, perhaps without realizing its full import. Germany's naval capability was pretty weak. But they couldn't very well back away from the table. Throwing down a card saying, "You better be careful, we'll sink your ships," seemed like bluff, and at first it may have been. Britain responded by calling Germany's bluff. "Oh yeah? You just try it, you bastards!" No one really thought they would.

Was that a reasonable assumption, especially when the chips on the table were the lives of hundreds of innocent people? Seen from the standpoint of 1915, it probably was. Nothing like the Lusitania disaster had ever happened before. The war in France was horrible and ugly, but aside from the civilians who lived there--most of whom fled, or tried to--those horrors were being faced by trained military men, not innocent non-combatants. (Most Britons weren't paying attention to what was happening on the Eastern front, where the impact on civilians was much more ghastly). A few months previously, at Christmas 1914, the British and Germans on the Western Front held an unofficial cease-fire and played soccer between the lines. There was still a sense of decency and fair play in war, or at least the officers thought there was. Most of the commanders on both sides came up through the ranks in the late 19th century, when Victorian morals held war as a sort of sporting contest, not all-out slaughter. They were, on both sides, tragically naïve.

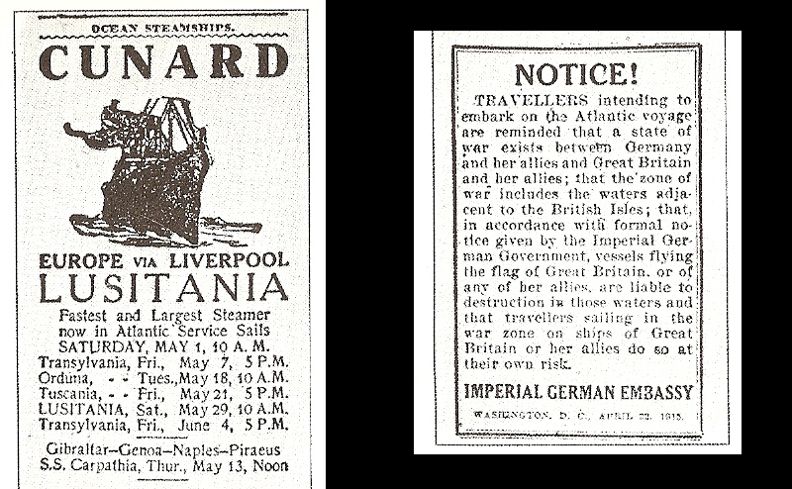

So that was how things stood when the Lusitania left Pier 54 in New York on May 1, 1915. The German Embassy had even tried to underscore the danger by running an ad in the New York Times warning passengers going on the voyage that they were sailing into a war zone. If they saw this warning, certainly not very many were swayed by it enough to cancel. Lusitania was not a warship. Conspiracy theories about what might have been in her hold aside, it was a huge stretch to claim that the world's largest passenger liner still in service was a military target.

A week later off the Irish coast Kapitanleutnant Walther Schweiger, the commander of the submarine U-20, just happened to get lucky. Everything went wrong for Lusitania: her Royal Navy escort stood her up, her captain made the wrong decision about zigzagging, and weather conditions were perfect for the ship to be spotted from a periscope. Furthermore, unbeknownst to no one, coal dust was floating around in Lusitania's almost-empty coal bunkers, which could easily ignite from a spark and blow the whole bottom of the ship out. When Schweiger and his men saw the unmistakable profile of the ship approaching, and at a speed and course that made a shot feasible, the sub captain was now handed the high card that the German nation was probably unsure it really wanted to play, at least not in these circumstances. After all, thousands of people could die, and there were almost certainly neutrals--Americans, specifically--among them. The whole course of world history might be altered. And the true nature of war in the 20th century might never be the same.

We can't know, but I suspect when he had to make that decision, Schweiger peered through the periscope, broke out in a cold sweat and asked himself, "Crap. Do I really want to do this?" Or perhaps, given his training and devotion to duty, he didn't think about it, and calmly gave the order to fire. It's hard to decide which is more monstrous. But in the long and tragic moral history of warfare, the Lusitania disaster was a grim milestone that helped make even more appalling massacres of the 20th century conceivable, and perhaps inevitable. This may be the true meaning of the Lusitania tragedy.

The Value Proposition

Why should you be reading this blog, or receiving it as a newsletter? This is why.

☕ If you appreciate what I do, buy me a virtual coffee from time-to-time to support my work. I know it seems small, but it truly helps.

📖 You could also buy my newest book.

🎓 Like learning? Find out what courses I’m currently offering at my website.

📽 More the visual type? Here is my YouTube channel with tons of free history videos.

Comments ()