The Battle of Dan-no-ura: Japan's medieval reckoning.

The great battle for control of Japan, fought in 1185, has resonated in legend for 800 years.

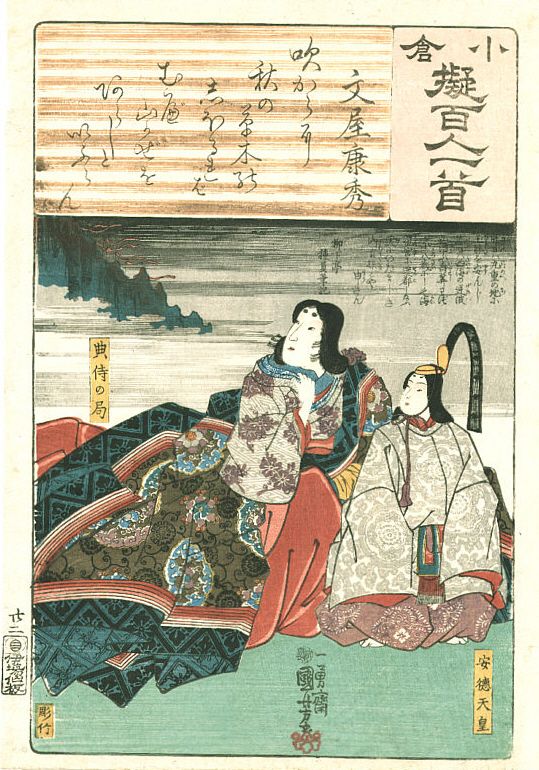

During one of the many great conflicts in Japan's long Middle Ages, two great warrior clans, the Taira and the Minamoto, duked it out for control of the island empire. After five years of war, their epic struggle came down to one final apocalyptic battle at a place called Dan-no-ura, on the Straits of Shimonoseki between the islands of Honshu and Kyushu, on April 25, 1185, 838 years ago today. This battle was rare in Japanese history in that it was primarily a naval battle. And like many great battles, particularly in this period, it became fuel for a body of tradition and cultural folklore that stretches over the centuries to the present day. For the record, it was the Minamoto who emerged victorious. Top commanders of the Taira, who held custody of the emperor--who was only a boy of six or seven at the time--began committing suicide when they realized the currents and tides had changed and the Minamoto ships were outflanking them. Legend has it that the boy Emperor Antoku was drowned by his caretaker and grandmother, Taira no Tokiko, rather than let him and herself be taken alive.

On many levels it's hard to separate historical fact from fiction and folklore regarding the Battle of Dan-no-ura and the Gempei War, the larger conflict of which it was the climax. What we know about this event comes largely from The Tale of the Heike, a written saga compiled in the 14th century, nearly 200 years after the event. Medieval sagas, whether from Japan or from Western countries (such as the classic Norse sagas), were less concerned with transmitting historical information than they were in illustrating a principle, vaunting a hero, or constructing the identity of the people described in them as well as the audiences at whom they were aimed. I have done both modern and medieval history, and in parsing the latter it's often infuriating how the facts of an event must be triangulated--or deduced--from one or perhaps a handful of unreliable sources. To put it in perspective, imagine trying to analyze the true story of the Battle of Stalingrad, 200 years after it happened, when your only source is a handwritten manuscript with missing pages and which itself might be either a Nazi or Soviet propaganda pamphlet. On the other hand, medieval history is often a fun and challenging puzzle precisely because of this dynamic. It also leaves us in the present considerable room for interpretation or reinterpretation.

Dan-no-ura was one of those battles that clearly was decisive. The Genpei War was not about who would sit on the throne of Japan per se, but rather who could claim political and religious legitimacy from the Emperor who did. After 1185, the Minamoto clearly held this legitimacy. A few years after the battle, in 1192, Minamoto no Yoritomo, brother of the Minamoto commander who won at Dan-no-ura, established himself as Shogun, or the military ruler of Japan. This government, which historians call the Kamakura Shogunate, ruled the empire until 1333. The Taira were utterly destroyed and largely vanish from history after the battle. Military government by the Minamoto clan was in many ways the blueprint for the Tokugawa Shogunate, the next period of Japanese unity, which was also cemented by a military victory--the Battle of Sekigahara in October 1600--and led to over 260 years of relative peace within Japan. Of course between Kamakura and Tokugawa there was a long period of disunity and civil war. This is the rhythm of Japanese history at least until the modern period. Thus, what happened at Dan-no-ura is undoubtedly important.

Several of the great legends that arose from this battle involve priceless artifacts with rumored spiritual power. Traditionally the Emperor of Japan held three objects, the imperial regalia that helped confer his power: a sacred sword, called Kusanagi no Tsurugi, a sacred bronze mirror called Yata no Kagami, and a jewel, a kind of sacred bead, possibly made of jade. When Taira no Tokiko jumped into the water off Shimonoseki with her grandson at the climax of the battle, it was said these three totems vanished into the waters with them. Supposedly the mirror and the jewel were recovered by divers but Kusanagi no Tsurugi, the sword, was lost. Nevertheless, a sword identified as Kusanagi no Tsurugi survives into the present day, perhaps a replica created at the end of the 12th century. Although it exists in the Japanese imperial treasury today--it made an appearance in 2019 at the coronation of Naruhito, the new Japanese Emperor--no one alive in the modern world has actually seen it. It's kept inside a clay box that's forbidden to open, and no one has done so since the box was refurbished by Shinto monks sometime prior to 1867. Due to its sacred status and enforced secrecy, we may never know whether the sword in that box is the original, a copy, or a copy of a copy. The idea of it is sort of a tantalizing MacGuffin, like the object of an Indiana Jones quest. There aren't many objects left on planet Earth in the year 2023 that have that sort of status.

There are apparently no physical or archaeological remnants of the Battle of Dan-no-ura, which I guess is not surprising considering it was a naval battle fought with wooden ships over 800 years ago. The zone where it was fought is one of the busiest waterways in Japan, constantly cris-crossed by ferries and watercraft of all kinds. Finding remnants of historical naval battles is notoriously difficult, and if anyone has ever gone down to the bottom of the Straits of Shimonoseki to search for medieval artifacts I'm not aware of it. It certainly would be magnificent to see what one of the Taira or Minamoto ships might have looked like. The fishermen of the Shimonoseki area believe that a certain species of crab, which has markings on its carapace that look like the face of a samurai warrior, contain the spirits of samurai killed at Dan-no-ura, and thus throw them back into the sea when they wind up in their nets. That too is folklore and legend. It would be quite a different thing to find a bit of ancient rusted metal from a sword or a helmet, some physical piece of this conflict from long ago.

As you can plainly tell, I'm fascinated by the Battle of Dan-no-ura and what it represents. History is such an intriguing realm of the mind and imagination, every bit as much as it is a discipline of facts, research and analysis. I would love to have gotten just a glimpse of what this event really looked like in the real world, even if it didn't match up to the expectations built up in my head.

The Value Proposition

Why should you be reading this blog, or receiving it as a newsletter? This is why.

☕ If you appreciate what I do, buy me a virtual coffee from time-to-time to support my work. I know it seems small, but it truly helps.

📖 You could also buy my newest book.

🎓 Like learning? Find out what courses I’m currently offering at my website.

📽 More the visual type? Here is my YouTube channel with tons of free history videos.

Comments ()